Publisher’s presentation

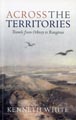

An initial mapping of this book might say that it goes from Orkney to Polynesia via Scandinavia and the Baltic regions, the Iberian peninsula and North America. It it’s impossible to sum up the diverse pathways and the multiple dimensions of White’s method in that highly original type of travel-writing he calls the waybook. The thing is to get out on the road with him. Along with, for example, three Quebeckers from the St Lawrence river-country through the forest and along the coast of Maine, or with an eleventh-century Jewish poet across Andalusia. Other chapters take the reader to the haunts of migrating cranes in Sweden, the misty margins of Portugal, across the plains of Poland, into the Atlas mountains, or along the coast of Norway into the Lofotens. The book ends on the atoll of Rangiroa in the Tuamotu archipelago, on a shore of dark jagged coral, wild birds cries and empty sea. The effect of travelling with White on his odyssey is an acutely increased sensation of life, a vastly enlarged experience of the world.

An initial mapping of this book might say that it goes from Orkney to Polynesia via Scandinavia and the Baltic regions, the Iberian peninsula and North America. It it’s impossible to sum up the diverse pathways and the multiple dimensions of White’s method in that highly original type of travel-writing he calls the waybook. The thing is to get out on the road with him. Along with, for example, three Quebeckers from the St Lawrence river-country through the forest and along the coast of Maine, or with an eleventh-century Jewish poet across Andalusia. Other chapters take the reader to the haunts of migrating cranes in Sweden, the misty margins of Portugal, across the plains of Poland, into the Atlas mountains, or along the coast of Norway into the Lofotens. The book ends on the atoll of Rangiroa in the Tuamotu archipelago, on a shore of dark jagged coral, wild birds cries and empty sea. The effect of travelling with White on his odyssey is an acutely increased sensation of life, a vastly enlarged experience of the world.

Extracts

At eight, I made my way along the bright green emerald hallway, down the musty darkbrown staircase, into the Dining Room.

Rosycoloured pillars. Goldfish in a case swimming in saudade (that « undefinable », as they say, Portuguese sensation of existence). A tray of cheeses slowly turning into Art Déco and a couple of flies showing their appreciation. On a mezzanine, a forlorn piano (flanked by four chairs for players of those Portuguese onion-shaped guitars) from which, perhaps, in the old days, fervently mellifluous fado was sung.

I ordered a dish of mullet.

The waiter was a moony kind of fellow with a droopy moustache. I’d talked with him earlier. It was a weird experience. I’d asked a question, nothing metaphysical (like “What is God ?”), nothing even existential (like “How are things, man”). Just a plain chronological : “When’s dinner ?” Time passed. The question seemed to have gone along a long mental labyrinth and got lost in the cosmos. I’d given up all expectation of an answer when out it came : “Thirty-seven”.

When the mullet turned up, they were as tough as tyres.

I called over the waiter and, in a quiet way, said :

“This fish, my friend, is overcooked.”

After I’d made my statement, a month passed. The goldfish felt taedium vitae weighing on them heavier and heavier, the flies got blasé about art and buzzed off into a bleak night of nihilism, I myself began to feel I had pronounced humanity’s last word, when the answer came :

“Ah, yes, it is always like so in Portugal.”

There’s fado for you, from the Latin fatum, meaning destiny.

Destiny, disaster and doom, not forgetting dire despair.

I poked stoically at the maltreated mullet for a while, drank a coffee at which the flies showed a reawakened interest in life, and went back up to my room.

The traffic was still busy and noisy.

Navarro’s Bar down below was offering Pizzas and Coca Cola.

The rain was falling heavy again.

Mondego Blues.

Extract from the chapter “Rainy Margins and Misty Horizons”

When I got to Porto, with its cluster of rosy-coloured houses, it was like a deserted village, a ghost town. Le Romantique was closed, L’Hôtel Moderne was closed, Le Robinson was closed. Everywhere was the sign : “End of season”. I liked that atmosphere (end of a century, end of history ?), even if it meant that it was difficult to find a place to stay. Anyway, I didn’t try too hard. I had my mind set on the village of Piana farther still down the coast. There I found a congenial room.

In the early morning, I climbed up the rock behind my lodgings, and looked out over the colours and shapes of all that superb volcano-plutonic complex I had before my eyes. How many contradictory forces have come together to create such an extraordinary mass of matter. It was as if floods of energy from the sun had taken on expressive shape.

That moment on the rock was my ultimate Corsican meditation.

As I took my breakfast on the terrace of my room, I noticed a swallow’s nest up in a corner of the roof.

The swallows had gone.

Extract from the chapter “Around Corsica”

Rosycoloured pillars. Goldfish in a case swimming in saudade (that « undefinable », as they say, Portuguese sensation of existence). A tray of cheeses slowly turning into Art Déco and a couple of flies showing their appreciation. On a mezzanine, a forlorn piano (flanked by four chairs for players of those Portuguese onion-shaped guitars) from which, perhaps, in the old days, fervently mellifluous fado was sung.

I ordered a dish of mullet.

The waiter was a moony kind of fellow with a droopy moustache. I’d talked with him earlier. It was a weird experience. I’d asked a question, nothing metaphysical (like “What is God ?”), nothing even existential (like “How are things, man”). Just a plain chronological : “When’s dinner ?” Time passed. The question seemed to have gone along a long mental labyrinth and got lost in the cosmos. I’d given up all expectation of an answer when out it came : “Thirty-seven”.

When the mullet turned up, they were as tough as tyres.

I called over the waiter and, in a quiet way, said :

“This fish, my friend, is overcooked.”

After I’d made my statement, a month passed. The goldfish felt taedium vitae weighing on them heavier and heavier, the flies got blasé about art and buzzed off into a bleak night of nihilism, I myself began to feel I had pronounced humanity’s last word, when the answer came :

“Ah, yes, it is always like so in Portugal.”

There’s fado for you, from the Latin fatum, meaning destiny.

Destiny, disaster and doom, not forgetting dire despair.

I poked stoically at the maltreated mullet for a while, drank a coffee at which the flies showed a reawakened interest in life, and went back up to my room.

The traffic was still busy and noisy.

Navarro’s Bar down below was offering Pizzas and Coca Cola.

The rain was falling heavy again.

Mondego Blues.

Extract from the chapter “Rainy Margins and Misty Horizons”

When I got to Porto, with its cluster of rosy-coloured houses, it was like a deserted village, a ghost town. Le Romantique was closed, L’Hôtel Moderne was closed, Le Robinson was closed. Everywhere was the sign : “End of season”. I liked that atmosphere (end of a century, end of history ?), even if it meant that it was difficult to find a place to stay. Anyway, I didn’t try too hard. I had my mind set on the village of Piana farther still down the coast. There I found a congenial room.

In the early morning, I climbed up the rock behind my lodgings, and looked out over the colours and shapes of all that superb volcano-plutonic complex I had before my eyes. How many contradictory forces have come together to create such an extraordinary mass of matter. It was as if floods of energy from the sun had taken on expressive shape.

That moment on the rock was my ultimate Corsican meditation.

As I took my breakfast on the terrace of my room, I noticed a swallow’s nest up in a corner of the roof.

The swallows had gone.

Extract from the chapter “Around Corsica”

Press

Here White wanders the world, taking us with him on his journeys from Orkney over to Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Poland, on to North America, Corsica, the Iberian peninsula, the Atlas mountains, and finally Polynesia. His movement is from the city out into the wild places, and on the way we meet dancing cranes, barracudas, white blackbirds, and all kinds of folk, including a shaman full of light. Out of it all come beautiful moments : “You have to go out. You have to open space and deepen place. Fill your eyes with the changing light” (Jutland). That area of energy and light opens up again and again.

White believes that the novel has had its day and that these live moments of “white-glowing sensation” and immediate experience of people and places […] can be conveyed much more directly in the “waybook”. It is a challenge which, so far, other writers in Britain haven’t taken up, save in the most defensive fashion, but perhaps this time his highly illuminating prose form will catch the imagination of a public who must be growing tired of dollops of more of the same old reheated fictional porridge.

Norman Bissell, The Scotsman

White believes that the novel has had its day and that these live moments of “white-glowing sensation” and immediate experience of people and places […] can be conveyed much more directly in the “waybook”. It is a challenge which, so far, other writers in Britain haven’t taken up, save in the most defensive fashion, but perhaps this time his highly illuminating prose form will catch the imagination of a public who must be growing tired of dollops of more of the same old reheated fictional porridge.

Norman Bissell, The Scotsman